Research Topics

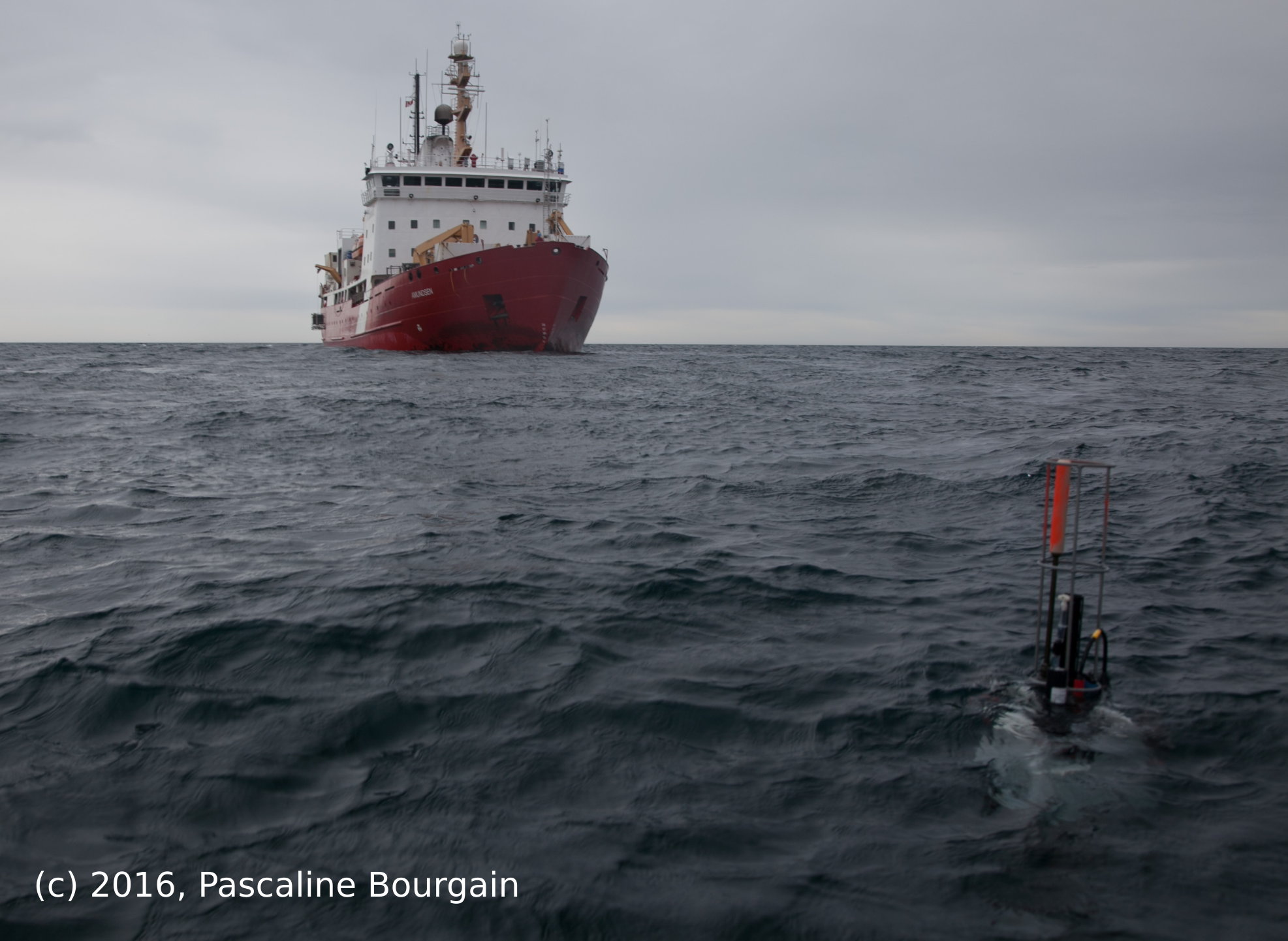

Bio-optical Argo floats

Remote sensing of the global ocean using satellites monitoring the state of marine ecosystems year-round. In the Arctic, the presence of sea ice and the long polar night are a showstopper for many of these approaches. Biogeochemical (BGC) Argo floats are autonomous robots that drift around with ocean currents, going up and down in the water column as they sample the world's oceans. The Takuvik laboratory that I am a part of has been deploying BGC Argo floats in Baffin Bay to study the year-round evolution of ecosystem dynamics, even during winter when satellites cannot look into the ocean.

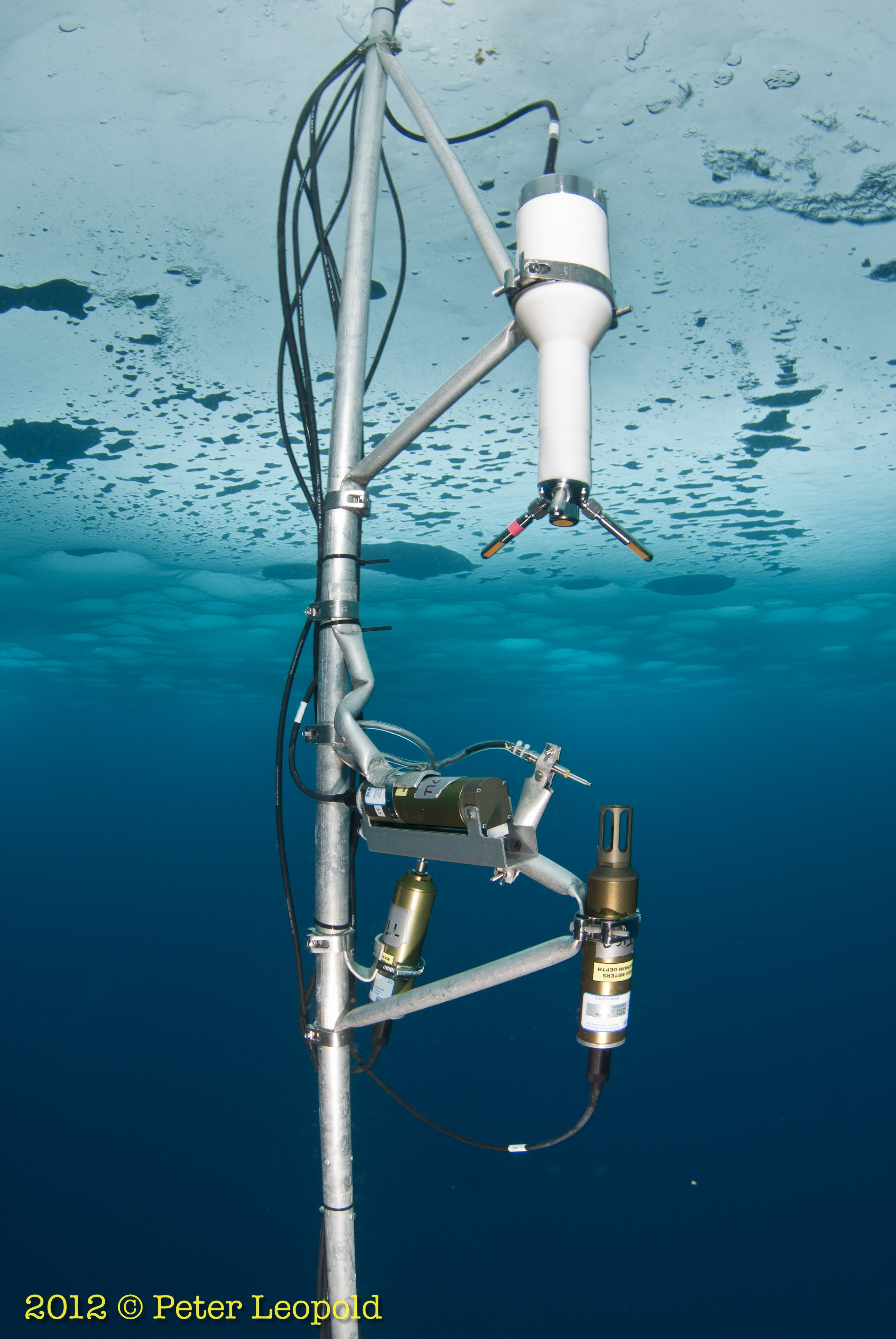

Vertical turbulent nitrate fluxes

Without regular vertical mixing, most of the world ocean would be dead and deserted. The reason is that algae have a tendency to sink and hence take scarce plant nutrients with them to depth. These nutrients' only chance of getting back into the sunlight, where algae grow, is when the ocean is stirred by winds, the tides, upwelling of deeper water, or other currents. Because of the huge amounts of river and other fresh water sources in the Arctic Ocean, the Ocean is especially resistant to such mixing. Hence large parts of the Arctic Ocean are among the nutrient-poorest regions of the world's oceans which drastically limits its productivity. My Ph.D. thesis was one of the first systematic attempts to measure this 'vertical turbulent nitrate flux' with a large in-situ data set collected from drifting ice camps, research vessels, and moored instruments.

Ice-ocean interaction

One of the most distinctive features of Arctic marine ecosystems is the presence of sea ice. It alters how wind moves around the water and how those currents mix the upper ocean; it changes the flow of heat from the atmosphere into the water and back; it changes the supply of spent surface waters with deep, nutrient rich ones; it changes the density of the sea water and hence the turbulent mixing of the very environment in which plankton lives. It is the lack of sunlight in winter that makes the water freeze, but it is the heat stored in the ocean that makes the ice not grow forever. All of these phenomena are what oceanographers refer to when they use the rather prosaic expression 'flux of momentum, heat, salt, and other tracers'.

Given its relevance for the Arctic summer, when plankton grows, I have been especially interested in melting sea ice. Melting sea ice creates a layer that resists vertical mixing, often a drastic change from the more intense mixing that happens in winter, which I explored in two studies in 2014 and 2017.